Serving in the CDC Response to Ebola in Sierra Leone

Above: Market at the Old Wharf in Freetown where freed slaves first returned in 1787, eventually contributing to the founding of the colony of Sierra Leone.

The following article, written by Terry Chroba '67, was originally published in the Spring 2015 Regis Alumni News magazine and details his experiences fighting the widespread Ebola epidemic in West Africa.

After spending 6 weeks in Sierra Leone working to combat Ebola, I finally have a moment to collect my thoughts, to try to describe a small part of the maelstrom of the Ebola experience. The world has watched somewhat spellbound over the past 16 months as “Ebola,” i.e., the Ebola virus disease, has had its most widespread epidemic ever in several West African countries. In the current outbreak, there have now been close to 25,000 suspected, probable, and confirmed cases and over 10,000 deaths reported. As in Liberia and Guinea, Ebola has caused significant mortality in Sierra Leone, with reported case fatality rates in excess of 40% over the three countries. In Sierra Leone, the donor community has aided in reducing transmission through assisting indigenous efforts in surveillance, early diagnosis, secure transport, contact tracing, hospitalization, and behavior change. What is still needed is a single-dose vaccine that would be safe and effective, and could be deployed efficiently in the resource-constrained African setting. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC), the National Institutes for Health (NIH), and the World Health Organization (WHO) are now involved in vaccine trials: CDC in Sierra Leone, NIH in Liberia, and WHO in Guinea. The NIH trial in Liberia is being conducted by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases under the direction of Dr. Anthony Fauci ’58.

As a career physician at CDC, I helped teach a CDC course last year in Anniston, Alabama, aimed principally for physicians and nurses intending to work in West Africa. The course covered the basic principles of the wearing of personal protective equipment (PPE) and safe clinical care and management in an Ebola treatment unit (ETU). My fellow faculty members included several returning-responder physicians and nurses who had worked in ETUs in which so many people, especially health care workers themselves, have died. Ebola has had its deepest effect in the health care worker community, which has been at high risk because of the infectivity of blood and bodily secretions, lack of availability or appropriate use of PPE, and challenges in following infection control and prevention protocols. Of all the reported Ebola deaths, more than 9% have been among health acre workers, with rates in excess of 100 times higher than in the general population.

Over a decade ago, I lived in Cote d’Ivoire, directing a facility with many projects focused on disrupting HIV transmission. Since the onset of the Ebola epidemic, I have longed to return to West Africa, to contribute, with the dream that we might find a long-term solution to the current crisis. Two countries over from Cote d’Ivoire stands Sierra Leone, a very beautiful but impoverished state. With a dense population, over 6 million spread across a land mass about the size of the Republic of Ireland, this land has had a failed, broken, recent past, with a civil war that began in 1999 and lasted over a decade. After unspeakable atrocities by the thousands, U.N. peace-keeping forces exited less than a decade ago. The legacy was more than 50,000 dead, much of the infrastructure destroyed, and over 2 million displaced as refugees in the neighboring countries. Trust in governmental interest in public welfare is only recent. Nature has been very unkind in targeting this population. As of mid-March, Ebola transmission continues, with 55 new cases reported in Sierra Leone in the week ending March 15, the majority of them being in the Northwest corner of the country where I have been working. Fortunately, the epidemic appears to be waning, with cases declining in 2015; in Liberia, the last identified Ebola patient expired on March 27. Unsafe burials have decreased in Sierra Leone but still occur, and many new cases are still being confirmed only after testing has been carried out on samples from persons after they died in the community, outside of treatment facilities.

In Freetown, I have helped develop a Manual of Operations with standard operating procedures for the CDC trial, with plans for health acre workers to be the majority of the trial participants. Several factors, including the gravity and magnitude of this epidemic and its relative restriction to West Africa, have greatly lent an imperative to our efforts here in the quest for a vaccine to control and prevent future epidemics. For the many dedicated members of the local population and the donor community working on vaccine issues, this has been a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to contribute so much in so little time, both to save lives and to find answers for the future.

Terry Chorba ’67 is an internist and a Branch Chief in the Division of Tuberculosis Elimination at CDC.

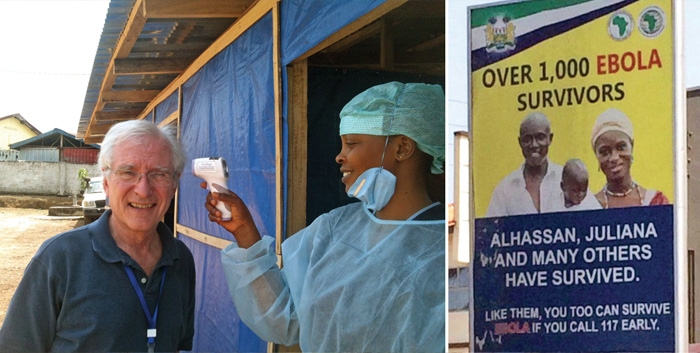

Above Left: Terry Chorba ’67 getting screened with a temperature gun on entering a hospital compound in Makeni, in the Northern District of Sierra Leone. Above Right: Poster from early in the Ebola epidemic, on the wall of a community clinic, advising how to obtain emergency assistance.

Read more Regis news